Osteoporosis In Men

Dr.Bharat Manchanda

Introduction

Fracture prevalence and incidence are different between sexes. This has been well documented in many epidemiological population-based studies. These differences are age-dependent. In growing children and young adults, the annual incidence of fractures increases temporarily, more in boys than in girls. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of fractures in children is an area of neglect. One-third of boys and girls sustain at least one fracture before 17 years of age. Fracture rates are 60% higher in boys than girls. The most common fractures in both sexes occur at the radius/ulna (30%). Peak incidence occurs at 14 years of age in boys and 11 years of age in girls. During young adulthood (25-40 years), fracture incidence remains low in both sexes. Later in adulthood, the burden of fragility fractures starts earlier in women than in men.

In men, the epidemiology of hip fractures is well documented, but the epidemiology of non-vertebral fractures is less well documented, although such fractures contribute substantially to the global burden of fractures in men. In white populations, about 20% of men older than 50 years will have a fragility fracture in their remaining lifetime. Fracture risk in men increases from 50 years on for vertebral fractures and from 65 years on for hip fractures. The lifetime risk for wrist fractures remains low throughout life. The number of hip fractures in men is expected to nearly double during the next decades in Europe. After the age of 50 years, the incidence of vertebral fractures is about one third to one half of that in women.

Mortality after fractures

Mortality rates after hip fracture are higher in men than in women. For example, in a Canadian health region, 71% if hip fractures were in women, 29% were in men. In-hospital mortality was nearly double in men (10% and 5% for women). Mortality at 1 year was 38% for men and 28% for women. Mortality after fracture is related to pre-fracture health status and post-fracture complications. When account is taken of co-morbidity, the death rates after hip fracture appear to be comparable in men and women.

Morbidity after fractures

In men and women aged 50 years or more, more than twice as many women were admitted to hospital for fractures. There are, however, similarities in terms of the pattern of hospitalisations. In a study in Sweden, hip fractures accounted for 63% of admissions for fracture in men and 72% in women and for 69% and 73% of the 600,000 hospital-bed days, respectively. Fragility fractures accounted for 84% of all hospital bed days due to fracture in men, and 93% in women.

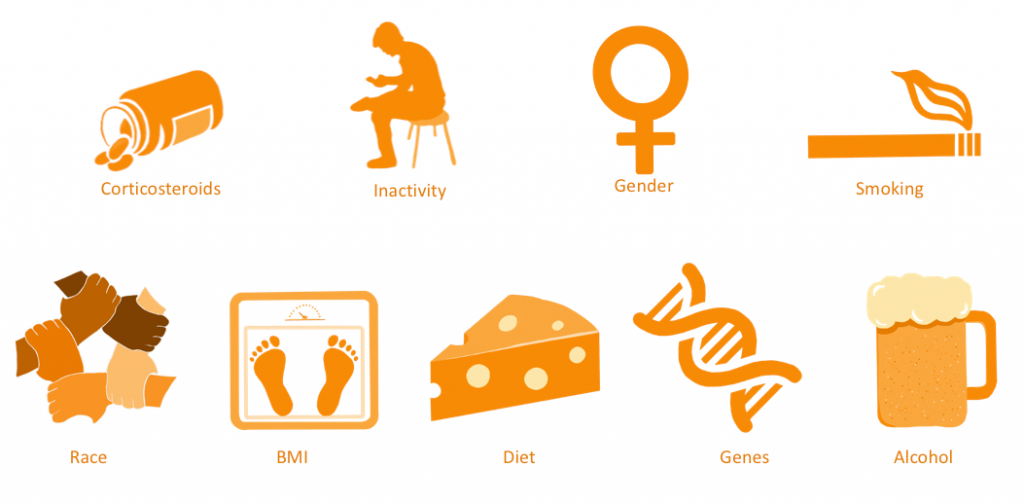

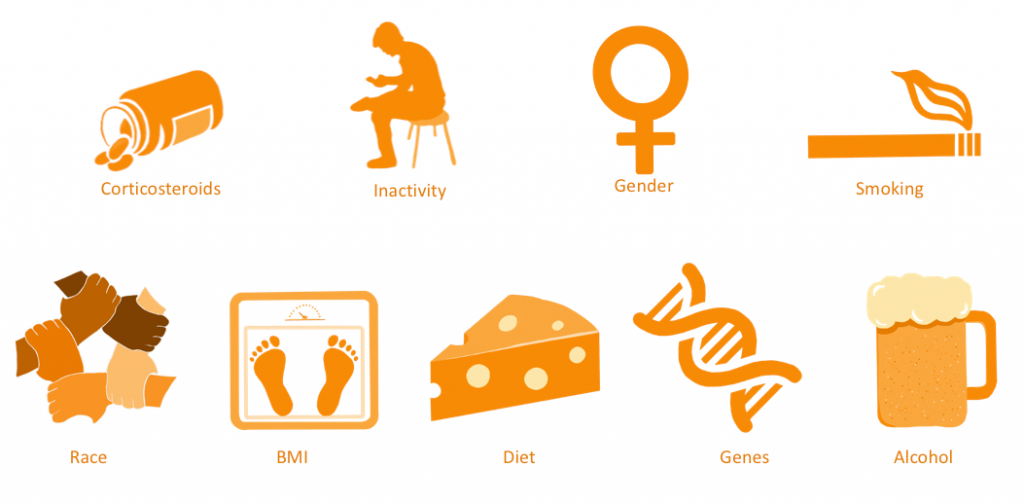

RISK FACTORS OF OSTEOPOROSIS IN MALES

The role of falls

Older community-dwelling women experience significantly more falls than do older men, and even after allowing for physical and social factors women are 1.5 times more likely to fall than men. Women living alone are at greater risk of falling and sustaining an injury.

Why do men fracture less commonly than women?

The bone site

At any adult age, a lower proportion of men have fractures than do women because the distribution of structural components that determine the breaking strength of bone is set above a critical level.

- Men build up bigger bones than women, this larger bone size being responsible for the higher bone strength. During aging bone size may increase in men more greatly than women by periosteal apposition, increasing the gender difference in bone size established during growth even further.

- Cortical bone loss is less in men.

- Trabecular bone loss is similar in men and women, but trabecular architectural disruption is less in men than women.

Young men’s increased bone density has also been partly explained by the extent of their participation in manual labour. However current demographic trends are suggesting that men are now more likely to be in similar jobs to women and have been found to be living more sedentary lives, which could decrease the rate of bone deposition and further add to the burden of the disease in later life.

Androgens, estrogens and the skeleton

Unlike women, men have no midlife decrease in sex hormone production and so no midlife increase in remodeling rate. The andropause is occurring at higher age then the menopause in women and only in part of the population of men. Aging in men, is accompanied by a progressive, but individually variable decline of serum testosterone production, more than 20% of healthy men over 60 years of age presenting with serum levels below the range for young men. Albeit the clinical picture of aging in men is reminiscent of that of hypogonadism in young men and decreased testosterone production appears to play a role in part of these clinical changes in at least some elderly men, the prevalence of androgen deficiency and its association with structural abnormalities is not unequivocally established. In fact, minimal androgen requirements for elderly men remain poorly defined and are likely to vary between individuals. Consequently, borderline androgen deficiency cannot be reliably diagnosed in the elderly.

Bone remodeling markers

Levels of biochemical markers of bone formation and of bone resorption are high in men aged 20 to 30 years, corresponding to the late phase of growth. After 30 years of age the markers decline reaching the lowest levels between 50 and 60 years of age. Formation markers remain relatively stable. Some markers of bone resorption increase after 70 years of age in men. Increased remodelling markers are independent predictors of fracture in men as they are in women.

Secondary osteoporosis

In contrast to women, in whom postmenopausal and age-associated osteoporosis are the most frequent causes of fractures, many men with osteoporosis have other causes than hypogonadism and old age. Especially in middle-aged men with osteoporosis, contributors to secondary osteoporosis are documented in up to 50% of cases.

The influence of glucocorticosteroids on bone density through the treatment of conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases is an instance where a more gender specific problem exists, due to the larger number of men affected.

Alcohol abuse is still seen to be a mainly male phenomenon, and its importance with the implications on bone loss is underreported and could have been highlighted as an area in need of further research and health promotion activity.

The role of smoking as a cause of bone loss is particularly important in men, though the number of young women now smoking should also be considered a warning of increased risk for them as well. A specific problem of secondary osteoporosis in men involves men treated for prostate cancer, in which androgen ablation therapy results in accelerated bone loss.

Idiopathic osteoporosis

Idiopathic osteoporosis, defined as osteoporosis that occurs without any known cause, is a rare form of osteoporosis that has been described in men under the age of 70 years. Its prevalence, cause and natural course are not well known.

Causes of Osteoporosis

Treatment

NON-PHARMACOLOGIC APPROACHES

- Diet

- Physical Therapy & Balance training

- Lifestyle Modifications

- Prevention of Falls

- Hip Pads & Other Assistive device

PHARMACOLOGIC INTERVENTIONS

- Calcium

- Vitamin D

- Calcitonin

- Bisphosphonates

- Parathyroid Hormone